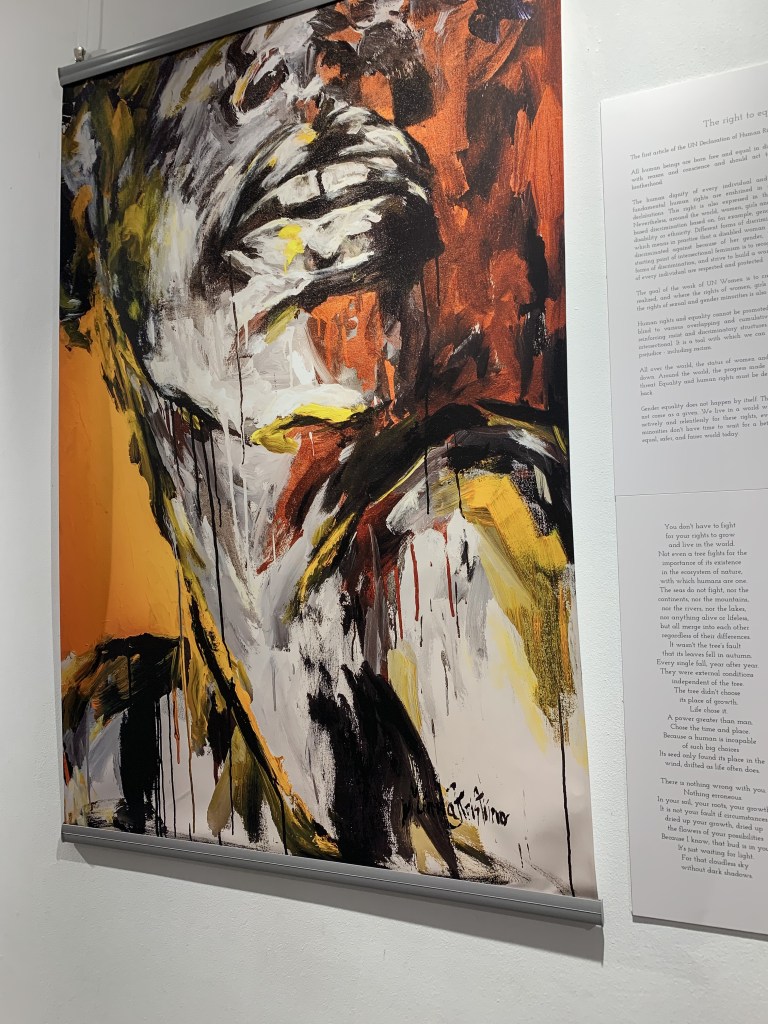

Painting: The Right to Equality by Minna Pietarinen

My interest in visual art has been in relation to how art brings about justice, transforms and documents culture and good old slice of life type of work. The work in the “I was born a girl” is a well timed reminder for women’s rights defenders to never lose hope. The exhibition was launched at the Goethe institute and HISA center, hosted by the Finnish embassy in honour of the 16 Days of activism against Gender Based Violence, taking place from the 24th of November to the 10th of December. I have no doubt that it was a worthwhile experience for anyone who appreciates art as a tool for justice. A project by Minna Pietarinene and Peppi Stunkel to highlight the incredible efforts of women’s rights activists and leaders from different parts of the globe. Each piece comes with a poem and corresponding human rights and their stories, succinctly capturing the efforts of some pretty awesome human beings.

Here some highlights from this exhibition;

Context from Namibian Human Rights Advocates

The event was launched with a notable mindfulness for the context of where it was being launched. The work has been showcased in different parts of the world, including Mexico, South Africa, Mozambique and Switzerland and it’s great to see that the project takes into consideration the conditions and background of its destination country. Created with the notion that while human rights are for everyone, they are not a ‘one size fits all’ solution.

Often times when the subject of human rights comes up, the risk of westernization disguised as human rights, especially because of the consequences of not being vigilant about intentional or unintentional colonial imposition. The need to guard contextual narratives is often a top priority when human rights are discussed because too many instances have come up where irrelevant solutions are applied. During the launch of this event, a panel discussion was held which included speakers from The Legal Assistance Center Namibia, UNFPA Namibia, Sister Namibia and the One Economy Foundation. The conversation highlighted an existing frustration with inadequate implementation of laws in Namibia, the need to expand on civic education and men’s engagement with Gender Based Violence Advocacy in Namibia. In response to this, a male engagement event in honour of the 16 Days of Activism against GBV was held on the closing day of the exhibition at the HISA Center. This exhibition was more than just a moment to appreciate some good artwork, it also provided a helpful platform to unpack men’s roles in advocating against GBV, the reality of having great written laws but not being able to use to rely on them, either as a result of people not knowing them well enough or regulators not always making use of them.

Photo: Standing next to the “My Dear Shame” piece by Minna Pietarinen.

The Works, the Poetry and the Women

What makes the “I was born a girl” exhibition especially universal is that the collection includes diverse women from diverse communities, all bound by uniting rights and theme. The colour orange is present in all the pieces, the colour of the Unite to End Violence against Women Campaign which encourages people to wear orange to symbolize a future free from violence. It starts off with an overaching experience associated with human rights violations, shame. The piece titled “My Dear Shame” speaks on how isolating and overwhelming such experiences can be, and how human rights are protective boundaries that make room for love, and how these rights can bring about positive change. The right emphasized in this piece is the right to safety and a life without violence. Other works include stories of women who intenetinally went into the profession of politics and the protection of human rights such as Sanna Marin the former Prime Minister of Finland who advocated for the right to non-discrimination. Women who inadvertently fell into advocacy by unapologetically pursuing their passions, such as Alcenda Panguana and Rady Gramane who became symbols for the right to gender equality in sports after challenging stereotypes in boxing. Women whose efforts as community workers highlighted rights violations, such as Zanele Mbeki whose commitment to social work resulted in her significantly addressing the right to economic empowerment.

The I was born a girl exhibition ran in Windhoek from the 13th to the 19th of November 2024 at the Goethe Institute and from the 20th to the 27th of November 2024 at the HISA Center. To learn more about this work, visit www.iwasbornagirl.fi .