***SPOILERS***

RATING: PG (Depictions of Sexual Assault)

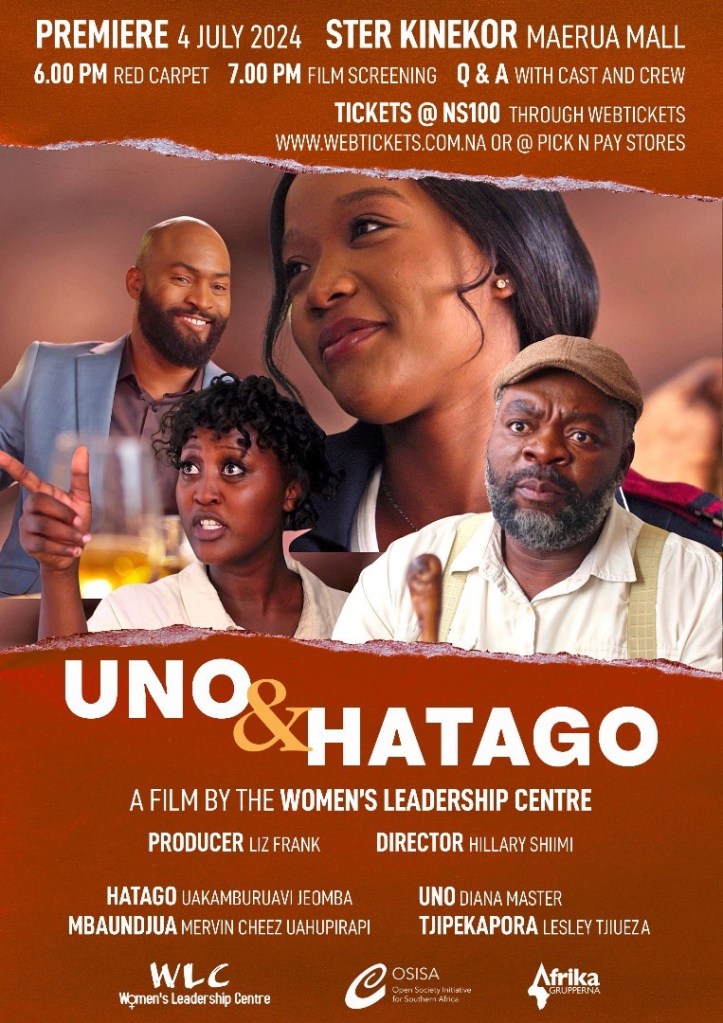

Uno and Hatago is an aptly timed production. It was largely marketed as a lesbian film, and it is, but it goes beyond that by addressing harmful cultural practices and promoting unity.

Uno and Hatago follows the story of a nurse, Uno, played by Diana Master, who’s world suddenly crashes when her family finds out about her sexual orientation. Up until then, Uno had been living in Windhoek with her partner Hatago, a feminist and LGBTQ+ rights activist played by Uakamburuavi Jeomba.

Patriarchy, Family Secrets and Tradition

The film is centered on how Uno’s family of OvaHerero traditionalists react to finding out that she is a lesbian woman. The traditionalism is explored from two ends. First is the ‘traditionalist’ idea that lesbianism is not acceptable or that is something foreign, and second is a traditionalism which acknowledges that lesbian women (and other members of the LGBTQ+ community) have always existed in Namibia and that true tradition is that this is not unAfrican.

The patriarchal nature of the first perspective is perfectly portrayed by Uno’s uncle, played by Mervin Cheez Uahupirapi, and her father, played by Lesley Tjiueza. These two played these characters so well, I left the theatre with so much animosity for fictional characters. The way they are written doesn’t stretch far from reality at all, the audience is likely to think of characters in their own lives who are like these two.

We meet Uno’s uncle during an intimate gathering at a restaurant, where they (Uno, Hatago and a few of their friends), have gone to celebrate Uno’s graduation. During that same night, Uno’s uncle is having dinner with his girlfriend, an extra-marital partner. His girlfriend insists on taking a picture of him, and as he protests this, he notices that she also captured his niece, Uno, kissing a woman right behind him. Suddenly his focus turns away from the possibility of being caught cheating to excitement having caught his niece in what he considers to be a cultural ‘sin’. He asks his girlfriend to share this picture with him and takes it to her father under the guise of taking immediate action to save the family’s reputation. His solution to this is to marry her off to Tove, his nephew with seemingly low marital prospects. The two agree on a dowry that Uno’s father can pay and thereafter, call Uno to the homestead to tell her that they found out about her ‘city life antics’ and about the marriage they have organized for her. In line with unspoken cultural norms, this uncle sexually assaults Uno to ‘prepare her’ for marriage.

Her father shows pride in his recently graduated daughter for her qualifications before completely discarding that in favour of viewing her as a shameful person. From the moment he finds out that his daughter is a lesbian, he focuses on hiding this “shame.” Essentially, it seems like, she is not truly successful if she does not let a man dominate her. He expresses this more by defending her uncle and disowning her after she reports the assault and carries on her relationship with Hatago. Embracing her lesbianism is a rebellion against the idea that she is not a real woman if she is not in a relationship with a man, just as being gay may be falsely viewed as not ‘real manhood’ if one is not dominant over a woman.

This form of ‘traditionalism’ which focuses on filling heteronormative and patriarchal templates completely undermines that dignity of women and this film explores this in a realistic way. The fact that Uno’s uncle was cheating is a non-issue while Uno’s committed and healthy relationship is. The fact that he has violated his niece is less of an issue than the fact that she is a lesbian, even to the police officer who recieves the matter.

It is Uno’s grandmother who sheds light on another of the other view of ‘traditionalism.’ The idea that lesbianism has always existed and that assault on women is an unacceptable norm. She helps Uno escape and return to the city after finding out that her uncle has attacked her, and the film ends with her sharing a story of a same-sex partner that she had before being married off to her husband. She shares about the grief she experienced when that partner passed away and the pain she felt not being able to express the extent of that grief given the nature of their relationship. She emphasizes togetherness through love and acceptance within a family, rather than allowing harm to go on, in the name of protecting family honour. She frames honour as being something that can come from showing up for each other rather than maintaining socially imposed images. In this case, the images of the ‘macho men’ and ‘high achieving, good girl daughter.’

Uno’s mother starts off with a similar stance to that of her husband. Rejecting her daughter because of her sexual orientation. However she gradually leans towards accepting her daughter after seeing that her family is becoming torn apart because of this, and worse still, that Uno’s sexual orientation has not stopped her from becoming a productive, successful and helpful member of society, or from having a child. Throughout the film, she maintains a regal and stoic disposition, not showing affection and avoiding vulnerability until it becomes clear that her husband’s stubbornness may force Uno to completely cut them off. This may have also been amplified when she meets her daughters mother-in-law, Buruxa (I hope I spelt that right), who shows unconditional love, encouragement and acceptance to Uno. Buruxa is the mother Uno needed and this may not have landed well with Uno’s biological mother. Soon enough, she takes on the grandmother’s stance, to lean into love and acceptance, while maintaining her rigid mannerisms. The character doesn’t change drastically, but in subtle ways like inviting Uno home and making her tea, and in her most expressive moment when she stands up for Uno to her husband, pointing out that his pursuit of family honour is fueled by hatred and that this is not the kind of family that can stay together for very long. She seems to represent anyone who has experienced this changing of perspectives, from a tradition rejection to one of radical acceptance.

Criticisms

Unfortunately we do not get to see Uno’s mother reacting to the assault and we do not get to see her express pride in her daughter’s achievements. We just see her expressing a whole lot of disappointment and coldness. Which can bring up the question of whether her distant nature is just who she is or if it came as a result of finding out that her daughter is a lesbian. Sure, Uno becomes tense when she notices that her mother is upset with her but the inexpressiveness seems to continue even after they have made amends, and seems to be there when Uno’s grandmother shares her story. It is not clear if we should expect affection from this woman if this is the personality she has always had or if she has taken on this persona as a reaction to Uno being a lesbian.

With the exception of Uno and Hatago’s friends whose cultural backgrounds and sexual orientations remain a mystery, the OtjiHerero heterosexual women we meet are all homophobic. On the other end of the scale, Buruxa, the only other woman we meet who is accepting of Uno and Hatago’s relationship, is of Damara heritage. Her sexual orientation doesn’t come up, but there would have been some reality balance in seeing a non-Herero speaking homophobe or a non-LGBTQ+, OtjiHerero speaking ally. This may come off as pitting the two customary groups against each other in how they view LGBTQ+ issues given that Namibia has the added context of tribalism and these two groups are mentioned on opposing ends of this issue. (But then again, the existence of this dynamic in this one story doesn’t mean there’s no alternative dynamic elsewhere, so don’t miss the plot by centralizing these criticisms)

Conclusion

More LGBTQ+ stories are needed in media, especially one’s like this one that humanize same-sex partners. Homophobia is just dispensed without consideration for the humanity of the people being attacked and the fact that they too are members of society (Just scroll through the comments section of any LGBTQ+ related post on the Namibian pages, it’s a mess). Beyond this, the authenticity of LGBTQ+ stories told by a predominantly LGBTQ+ production team didn’t go past any of the audience members, and likely contributed to how impactful the overall story is. The story touches on other themes that are not LGBTQ+ centric such as family, harmful cultural practices, civic action, women’s rights, gender norms and romance (I didn’t get into it but Hatago is such a supportive and loving partner, they’re a wholesome couple which makes it so much easier to root for them. The way their relationship is depicted is enjoyable and if not for the political aspect of this movie, you may want to watch it for the romance story.)

Definitely a must watch.