WHUDA (Winfried Holze Urban Design Architectures) a marble artworks studio which was started by Winfried Holze in 2018. It has since become one of the few marble arts companies actively preserving and transferring the art of stonemasonry.

Stonemasonry has, in the past decade, been cited as being amongst the fading forms of indigenous knowledge in Southern African countries. The Great Zimbabwe Museum, with the support of the Endangered Material Knowledge Programme, has been particularly focused on conserving the knowledge around dry stone masonry and encouraging a movement to reinvigorate the practice. It is an understatement to say that patronising this craft is a positive step in cultural appreciation.

The WHUDA team not only preserves this craft as artisans but they extend this skill to explore contemporary social narratives as well.

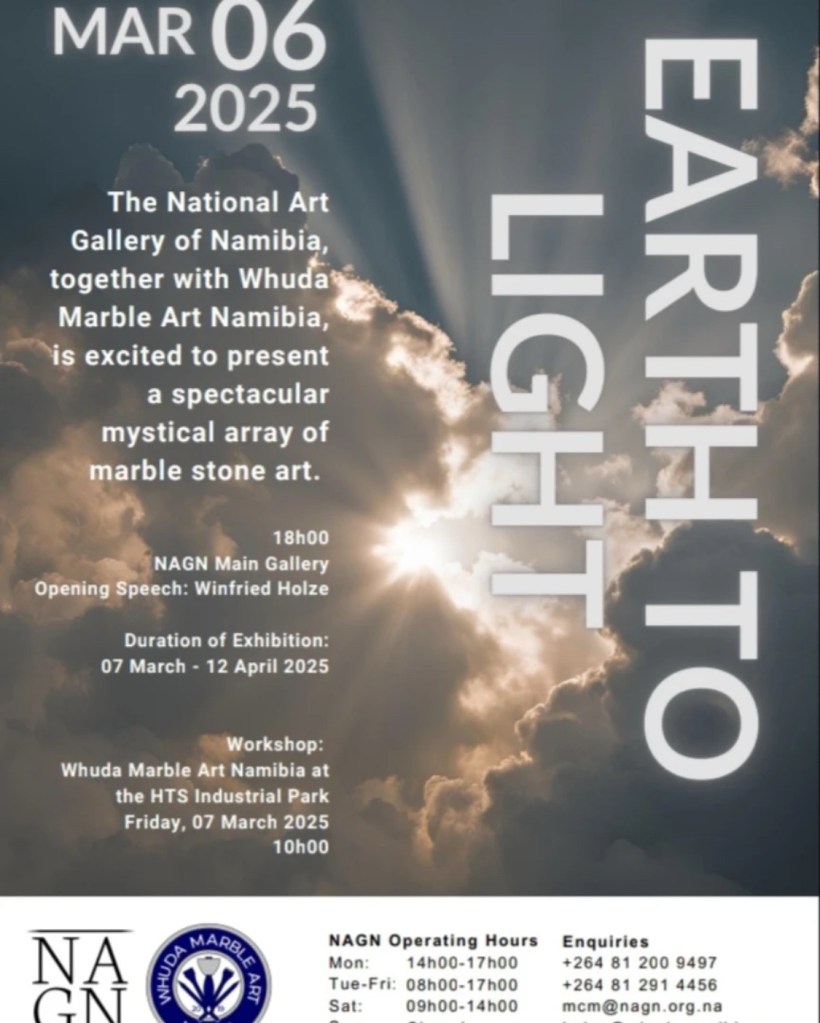

On the 6th of March 2025 the National Art Gallery of Namibia will be hosting WHUDA in an exhibition titled “Earth to Light” and the possibility of seeing some great works while exploring some insightful themes is palpable. The team’s recent works include an exhibition during KIFA Week 2024 (Kalahari International Festival of Arts), where the WHUDA team showcased works inspired by cultural integrity and mental healthcare which are very crucial subjects in our globalised world. Their latest work, “Silhouette Evolution” was a multidisciplinary event which portrayed the potent role of stonemasonry in contemporary arts and culture. Here’s a dive into that event;

Silhouette Evolution: Stonemasonry on perception and transformation

On the 25th of January 2025, I had the exciting experience of attending the Silhouette Evolution live session by William and Ino Ati. A silhouette is an image often in a single hue and tone against a brighter background, usually a black shadow against a white backdrop. Evolution has to do with the gradual development of something. This event made use of these concepts to explore perception and transformation.

This was the scene of the event; a painter painting the image of a sculptor who was in the process of sculpting while the audience dipped in and out of observing that process. Going to add their strokes on two group paintings that were in the next room, having conversations and drinks or playing a game of pool. Meanwhile, the stone being carved, the reason we were all there, was going through its transformation amid all these activities.

This event was without a doubt, an insanely creative way to explore the nature of transformation. That the world doesn’t stop to watch you change and grow, you just do as the world goes on, so that Pinterest quote saying “Stop waiting for the right time, and just start working on being who you want to be” has some truth to it.

In terms of perception, it seemed, the idea of a silhouette captures this very well. Fundamentally “what is your single hue image as everything else falls in the background?” and that “simply because it’s not the center of your perception doesn’t mean it loses value or ceases its own evolution” (your main character is not the only main character).

The event masterfully showcased three ideas associated with perception;

- That it is uniquely held; different people may look at the same things yet walk away with different ideas of it.

- That to be perceived is not a requirement of transformation.

- That what we perceive to be of highest importance is often what shapes our experiences.

While the audience simply watched a man turn a rock into a rock shaped like an owl. The painter created a much more dynamic image,capturing the sculptor’s movements while centering the owl with yellow eyes emerging from a block of marble. I mention the stonework as being at center stage, but, gathering from the painting titled “The sculptor’s nest” it could easily be the sculptor’s immense focus around all the movement and noise that could be said to be the crowning piece of the event, or the painter’s creative eye and craft in his portrayal of the transformation taking place in front of him that were the event’s masterpieces, or the paintings in the next room that the audience passively worked on together with less attention given to them until the sculpture was done. Or someone could’ve walked away remembering the owl in the painting and how it’s yellow eyes were watching us, and the guys playing pool could be looking on the day they had a great game of pool which stopped because it rained.

Ultimately, the title Silhouette Evolution perfectly captures this idea of a fantastic transformation taking place in the background. The question of which fantastic transformation takes the forefront depends on the viewers perspective, at the same time, that single perspective doesn’t lessen the value of the other transformations taking place.

Conclusion

Go visit the exhibition on the 6th of March 2024 at the NAGN to experience WHUDA artworks. The Silhouette Evolution is only one of the many means of storytelling and exploring of concepts that the WHUDA team has participated in. As they continue to contribute to the preservation of stonemasonry as an art form, their creations and the narratives they explore effectively document the times in culturally specific forms, while having the potential to address several contemporary issues.

Reach out;

WHUDA:

Instagram: @whudamarbleartnamibia

Website : http://www.whudamarbleart.com

Ino Ati (Painter of “The sculptors nest”) : @by_ino_ati (instagram)

Shamoulla (Coordinator of the group paintings): @shamoulla_creating (instagram)